A Portrait that Needed to be Three: Painting Tim

Oil on canvas, 87 3/4" x 114 1/8"

When Tim Jones and I first talked about a portrait project, just about a year ago, the pose I had in mind was of Tim at work. In Pine Plains and neighboring communities, Tim is well-known as a sixth-generation blacksmith who uses his formidable skills in the design and production of beautiful metal furniture. I could see a painting of him in his workshop studio, near his forge, anvil, and other tools. I even had a master painting to inspire me: The wonderful painting on the left by Velazquez, Apollo Visiting the Forge of Vulcan (1630). Velazquez's placement of people in the space where they work and his addition of work-related objects tells a story. It suggests psychological complexity and creates direct appeal in the painting (but no, I was not thinking of including a visitation by a god or many shirtless men).

I had also recently completed a portrait of Ralph Boekemeier, another famous resident of Pine Plains, at work. Ralph had found very meaningful and rewarding his work as a master carpenter. He and I had tried out many poses but it was only after he said that he would like to be painted with his tools that something clicked. I moved my easel from the studio into his basement workshop and we were able to capture the right pose -- Ralph at his drill press. Why not do Tim at work and launch a series called something like "Pine Plains at Work?"

Oil on linen, 20" x 24"

But it was not to be, at least not this time. The more Tim and I talked, the clearer it became we would go beyond an image of someone at work. Tim wanted the portrait to be a broader statement about who he understands himself to be, especially for his son; and painting him just at work -- Tim as blacksmith/Tim as artist -- was to put him in too small a box for what he would call his identity. He talked about there being more to his life than work. His love of nature and being outdoors needed to be part of our project. Arrows and antlers had to be in the painting. Tim said he could see himself posing in front of a favorite large green and grey lichen-covered rock on the mountain where he lives. He was so convincing about this that, in spite of the cold December weather, we went off to the mountain. It was indeed a great rock and he did look right in front of it. But I had my worries. The plan was to begin the portrait in mid-April and finish it in time for the Hammertown summer exhibition. How could we be sure of a sufficient number of comfortable days of dry and warm enough weather to work outside? Also, the pose was on a mountain. How would I get myself and all my painting gear up the side of this mountain? How would and I and my stuff stay put on this mountain? Tim's offer to build a platform on which I could paint couldn't be reassuring enough, given how much I move around as I paint, especially back and forth. So, we went back to talking about what we might do in my studio to capture something of the outdoors, and also to address Tim's idea that there was "more to his life" than what just one pose would suggest.

During the winter months, I worked on ideas for the spring painting of Tim. I looked at many other portraits. But it was by accident, in a literary magazine, Times Literary Supplement, that I came upon the portrait painting that just stopped me in my tracks.

Oil on canvas, 20" x 31"

On the left is Portrait of a Goldsmith in Three Views (ca 1529-1530) by the Italian artist, Lorenzo Lotto. It seemed perfect for the project with Tim. It was a portrait of an artist/artisan and it spoke to the issue of the need for more than one image of a person. In this painting, Lotto made the point that painting could be just as good as sculpture at showing the fullness of human form. I wasn't interested in the painting versus sculpture debate but I was very drawn to how Lotto had put on canvas the psychological idea about the multiplicity of identity: people are not captured in just one pose or view. Lotto's painting of the same subject from three different angles was the first of its kind. (If you want to know more about Lotto and his painting, see Roderick Conway Morris' review of a recent exhibition of his work in Rome, click here for the review).

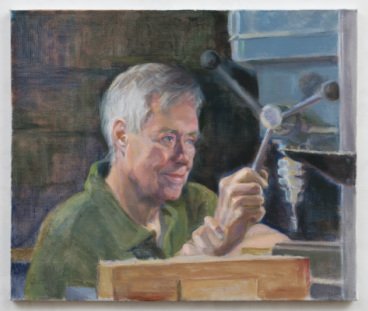

When Tim and I got together again in April, I showed him this painting and we talked about recent research in psychology on self and identity. We covered ideas like those about fluidity in identity and about how people negotiate their many identities while they simultaneously seek to hold onto some sense of unity and coherence of self. Tim connected with these ideas instantly. We were soon onto talking about how many and which of his many identities we would place on the canvas and what else we would put into the painting. It all fell quickly into place. Without lots of words, we decided: the identities would be three. They would represent Tim, the outdoors person in the central position; Tim, the artist/artisan, the image I had anticipated and knew what most folks would expect, on the right; and on the left would be Tim, the man who needs to go out into the public to promote and sell the work he designs. Also effortless was our selection of clothing and props for each Tim. He sat in one place in the studio, just changing into the right clothing and props for "each Tim," and I moved my easel around the room. Here is what we came up with through our collaboration, Portrait of Tim Jones in Three Views: