Ad Reinhardt, David Zwirner Gallery, Nov 7-Dec 18, 2013, NYC

Thanks to the wise suggestion of my visiting Canadian friend Fran Cherry, we saw a wonderful exhibit of work by the painter, Ad Reinhardt (1913-1966). On display are his satire, cartoons, photography, social and art criticism, and glorious paintings. You can visit the website (click here for that site). Better though would be to go the show and see things up close.

Learning more about the period in which he worked is always a good thing. I am fascinated by how postwar and through the 1960s, New York grew into an international art capital. It's now hard to believe that early in Reinhardt's career, there was only small group of painters, most of them working in the village, and just a handful of galleries. That, however, drastically changed. It is easy both to yearn for the "good old days" of a recognizable community and reasonable art prices, and be impressed by how American artists came so quickly to center stage. Reinhardt was there for it all. He left a remarkable record of the change and his strong feelings and thoughts about it.

Also appealing about this visit was the chance it gave me to see links between Ad Reinhardt and the late painter Saul Lambert in whose East Village studio I now work. Reinhardt was one of Saul's teachers when Saul was a student at Brooklyn College.

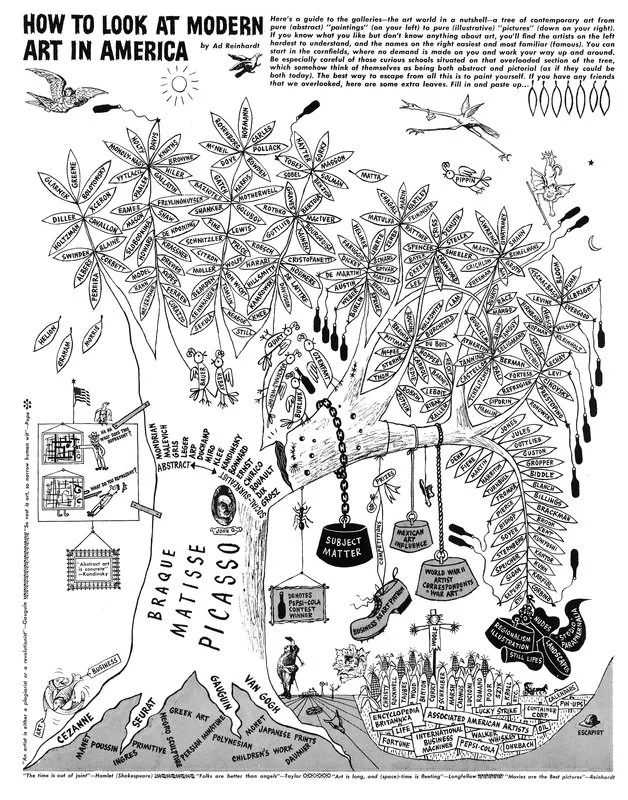

The exhibition at Zwirner takes up three rooms. The first large room that you enter is chock full of his graphic work, on the walls and in two large cases. It includes political and art historical satire and commentary (with biting critique of both European fascism and American capitalism), essentially all of it presented as cartoons and a little collage. There are his marvelous drawings of trees through which he shows us "How to Look at Modern Art in America." Each leaf represents a contemporary painter, the many varied clusters of leaves are all supported by the roots and trunks that Reinhardt also labels. He graciously leaves viewers some blank leaves on which they might tag and locate their own favorite painters. Here is one of those trees.

In the second room, a side room, one finds a large screen on which is projected a slide show made of a set of Reinhardt's collection of 12,000 slides. Most of these images are photographs that he took, often during his world travels (a smaller number are reproductions from magazines and museums). These are not your typical tourist photos. Actually, you get a hint of their uniqueness in a case from the first room, in a sketch book that Reinhardt kept while traveling in Italy. It is open to two pages filled with the tops of telephone poles. Yes, telephone poles; not the usual cathedrals and landscapes. The poles like all the other things that captured Reinhardt's unique eye are beautiful forms. What you see on the screen are all sorts of forms. For example, one will see a long series of roof tops. Then there is a series of faces with prominent eyes that suddenly shifts to a series of pairs of windows. The slides move through and back and forth across centuries and geographical locations. He projected these slides on any surface available in his classes and for discussion of art with his friends. Watching them come onto the screen, one after another in quick succession, is a delight. I became so aware of his distinctive way of seeing the world; and I also could feel how his perception was shaping my own. I can say that I will never look at a pair of windows in the same way again. And I am glad for it. It is impossible adequately to describe these slides. Go see them.

The third and final room contains a set of Reinhardt's famous black paintings. These are magnificient. In each, Reinhardt has a special way of capturing light in the darkness and using various colors to create what we call black.

After all the busyness and crush of the marks in the first room's graphic work and the extraordinarily varied and complex images of the second room, there is a welcome peace and expansiveness in these paintings. In looking at them, I saw an artist who simply loved paint and the act of painting. I will go back and just sit in the room to have his company.

Now what about the links between Ad Reinhardt's work and that of Saul Lambert, whose spirit keeps me company in the studio? I would love to find a notebook in which Saul recorded his class notes and the painting ideas he was inspired to have by Reinhardt. Missing that, I can only make a couple of observations.

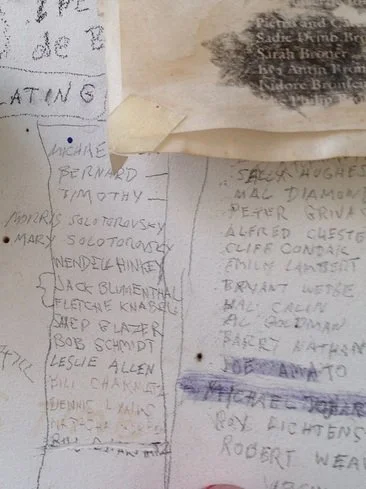

First, there are the words. In Saul's studio, one wall is covered by words that Saul composed or that he quoted from others. They include lists of names, not unlike the lists of names in several of Reinhardt's pieces.

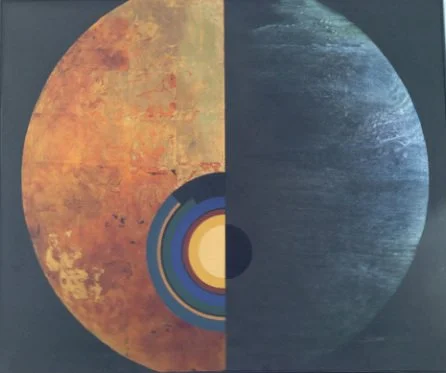

And then, there is the blackness. Many of Saul's paintings are also filled with black. Most have black grounds on which Saul paints abstract forms that often represent grand celestial spheres. I wish I could ask him both about the black and why he chose to add to it.

And wouldn't it be wonderful to know what Reinhardt would say about the work of his former student, another true lover of painting. My image of heaven is of a place where there is lots of talk about painting.

But in the meantime, please make your comments here. All will be appreciated.