Pieter Claesz (1597/98-1661) in My Studio

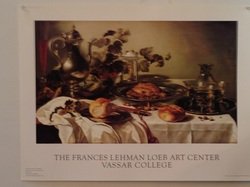

At left is a reproduction of the oil painting, Still Life with Fruits and Bread, 1641 by the Dutch painter, Pieter Claesz. I saw it up close at the wonderful Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center at Vassar College. The image may be clearer if you click on and visit the Center's website: (http://fllac.vassar.edu/collections/medieval_renaissance_baroque.html).

Claesz is a master of still life painting. He presents a highly naturalistic scene yet his work is filled with symbolic references. His objects reflect the grand and glamorous but also remind us of the inevitable passing of time (the watch in this painting and the nuts cracked open), and its link to human mortality (many of his paintings include a human skull). When I saw this painting at Vassar's gallery, I was struck by the extraordinary technique, the amazing use of light and dark, and of course the reflections seen on the metal and glass surfaces. I am fascinated by what we see both "on its own" and through something else.

This reproduction of Claesz's painting has hung in my studio for nearly three years. One recent day, it made it's way off the wall and came to pay a visit by my easel. I set up a new still life and enjoyed how Claesz's work inspired my choices.

Letting Claesz be my guide felt easy in many ways, like a simple matching process. The white cloth, some of it smooth, some of it bunched up, easily fell into the foreground. The bunched up part provided a nice painting opportunity. I could capture folds and creases through contrast of lights and darks and subtle variations in color. I set up the middle and back ground to be darker in tone. I filled the middle ground with lots of objects, many many more than I typically include. With those, I aimed to capture the same spirit of hospitality that Claesz invoked, welcoming guests to a party with food and drink almost ready for consumption.

But then, the connection with Claesz began to weaken. Try as I might, I couldn't put in as many objects as he had without the painting becoming oppressive. And I couldn't make it as dark as he had. Three hundred plus years have done a lot for lighting. Our eyes are not accustomed to seeing things in such a dark space as his. And then there are those specific objects. I couldn't imagine serving and or painting Claesz's roasted bird, with lumps of fat under the crispy skin and head and feet still attached. Also, the symbolic value of many of his items would escape most current viewers. I doubt that anyone looking at my pistachio nuts (right lower side of painting) would think of the passage of time and mortality.

So, along with the many links across the long sweep of the history of still life painting, there are differences. I think we can celebrate both.